Mindfulness-based approaches have been shown to be effective in improving the mental health of parents of youth and adults with autism and other developmental disabilities, but prior work suggests that geography and caregiving demands can make in-person attendance challenging. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability and preliminary outcomes of a mindfulness-based group intervention delivered to parents virtually. It was feasible to deliver this manualized intervention. Twenty-one of 39 parents completed the intervention and completers reported high satisfaction ratings. Parents reported reduced levels of distress, maintained at 3-month follow-up, and increased mindfulness. Changes reported following intervention were similar to changes reported in a prior study of parents competing an in person mindfulness group.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Priorities of autistic people and family carers (Ontario Brain Institute 2018; Pellicano et al. 2014) and clinical guidelines (Sullivan et al. 2018; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2011, 2012) suggest that mental health interventions need to target not only autistic adolescents and adults, as well as those with other developmental disabilities, but also family carers. Indeed, the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and overall distress is higher in parents of adults with autism and other developmental disabilities relative to other parents (Lunsky et al. 2014). However, there are few interventions targeted toward parent mental health.

Mindfulness, paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally (Kabat-Zinn 2003, p. 145), is associated with positive mental and physical health in diverse populations. Empirically supported mindfulness based interventions, such as mindfulness based stress reduction or mindfulness based cognitive therapy, teach both formal (e.g., body scan, breath meditation, walking meditation) and informal mindfulness practices (e.g., noticing sensations while brushing your teeth) and typically include learning a new practice or mindfulness skill in session followed by discussion (inquiry) about the experience and independent rehearsal of the activity as homework. Typically these skills are practiced by listening to an audio-recorded guided meditation exercise similar to the one taught in session. Recent systematic reviews (Cachia et al. 2016; Donnchadha 2018; Hourston and Atchley 2017) and a meta-analysis (Hartley et al. 2019) reported that mindfulness-based interventions may be effective for parents of autistic people in reducing stress, and improving overall well-being.

Existing research on mindfulness-based interventions has tended to focus on parents of younger children as opposed to older autistic adolescents and adults. Parents of older individuals may benefit from mindfulness because of the chronic stress they have been exposed to over time, their own emerging health issues that come with age, combined with the many gaps in services that autistic adults experience once school ends (Lunsky et al. 2015). In the only mindfulness-based group Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) targeting parents of older adolescents and adults with developmental disabilities (50% with autism), parents reported reduced depression and stress when compared to an active psychoeducation control, and these reductions were maintained at 3-month follow-up (Lunsky et al. 2017).

Unfortunately, not all families can commit to multi-week, in-person interventions because of caregiving demands and systemic barriers (Stjernsward and Hansson 2019). Further, specialized mindfulness-based skill groups for family caregivers are typically only available in larger communities, creating barriers for those living in rural or remote areas. Even if families can access in-person mindfulness training targeted toward the general population, a general mindfulness program may not be as effective as a program that is oriented to fit parents’ unique needs. Such tailoring may include practicing with other parents in a similar situation, and with modified exercises and expectations to accommodate their intensive caregiving responsibilities (Lunsky et al. 2015).

There has been increased attention in the mindfulness literature to delivering interventions virtually (Mikolasek et al. 2018), and a general trend toward promoting technology facilitated interventions and telemedicine as one way to improve access to mental health care, and reduce health care costs (Gentry et al. 2019). Mindfulness based instruction can be offered virtually through both synchronous and asynchronous means. Synchronous delivery means that everyone taking part is doing so at the same time, similar to an intervention being held in person, whereby people can see and hear each other’s responses in real time. An asynchronous intervention can be held individually or in a group, but group members need not be present at the same time. It can involve everyone viewing a recording or completing an exercise within a given time frame and sharing reactions to it with other group members and the facilitator. Asynchronous approaches offer the advantage of flexibility to set the time of participation and the pace of learning. There are several Apps freely available (Mani et al. 2015) and a number of studies showing that asynchronous instruction (whether individual or group based) can be beneficial to a number of user groups (Mikolasek et al. 2018), including autistic adults (Gaigg et al. 2020) and parents of people with developmental disabilities (Flynn et al. 2020). However, the asynchronous format, whether individual or group based, does not allow for real time feedback from the instructor, nor does it allow the same group of participants to interact as a group with one another at the same time (Fish et al. 2016). This is particularly relevant to mindfulness training, as the inquiry process, fundamental to mindfulness instruction, is best done within a group, with immediate feedback (Crane et al. 2015). In addition, in group-based mindfulness interventions participants have the advantage of learning from others’ experiences. There is also a secondary benefit of reducing one’s sense of isolation through meeting others in similar situations. This is of particular importance to isolated family caregivers.

Synchronous virtual interventions may offer the same advantages as in person interventions, with the exception of being in the same physical space. A recent systematic review of group based virtual interventions in general (Gentry et al. 2019) concluded that such groups are feasible and produce outcomes similar to in-vivo treatments with high participant satisfaction. Only one of the 40 studies reviewed, however, focused on a mindfulness or acceptance-based program offered to family caregivers, in this case parents of children with a life threatening illness (Rayner et al. 2016). Four other programs (of the 40 reviewed) focused on caregivers, and offered either psychoeducation or peer support. Although researchers have demonstrated the effectiveness of telemedicine more broadly within the autism community (Knutsen et al. 2016) with high rates of parent satisfaction, the focus has typically been on the autistic person or on teaching parents skills in relation to engaging with their child (e.g., Pennefather et al. 2018). To our knowledge, researchers have yet to explore the feasibility of virtual synchronous group-based mindfulness interventions specifically with parents of autistic youth and adults.

To address barriers to in-person mindfulness-based approaches, we modified the group based mindfulness intervention described in Lunsky et al. 2017 for online synchronous delivery (described in the 'Methods' section). Delivering the intervention virtually enabled therapists to bring together older parents from across the country using a freely accessible and virtual meeting space, to provide live therapeutic experiences in participants’ own homes. The current study was designed to answer four questions:

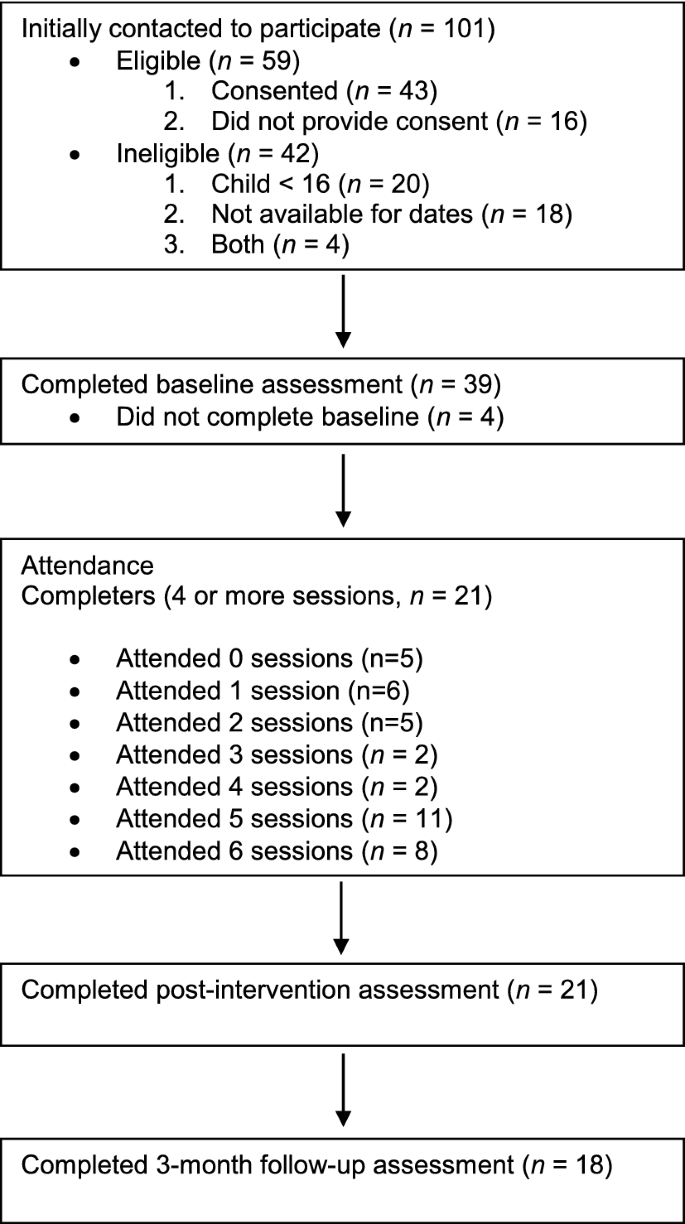

Participants were 39 parents, primarily mothers, of adolescent and adult-aged autistic sons and daughters from seven provinces in Canada. To participate, they required access to a computer, tablet or smartphone. Demographic information for this sample is presented in Table 1.

Satisfaction ratings of participants, completed at post-treatment, were consistently high in terms of utility of what was learned and applicability of information (Table 2). Total satisfaction scores for intervention-specific questions were high (M = 42.71, SD = 2.80) and similar to total satisfaction scores reported in the in-person study (M = 40.21 SD = 9.02). Parents rated items highly about the virtual mode of engagement, with the highest scores given for ease of use of technology, and convenience of online engagement. Scores were slightly lower for comfort with web-based technology and technological issues. Almost all parents rated that the felt connected to other parents. The majority of parents (14/18) endorsed that inclusion of the closed Facebook group for parents was useful.

Table 2 Parent feedback on group experience (n = 18)Parent responses to open-ended questions about what they liked best about the program and challenges they experienced fell into three themes: the value of connecting with others in similar situations, the benefits of and challenges with technology, and the utility of mindfulness-based skills.

Many parents highlighted that connections with other parents were important. For example, parents noted: “I like the fact that I was with a group of women that seemed to live similar challenging lives involving kids/persons that weren’t mainstream and required a different approach.” and that: “I was very grateful to have the opportunity to learn these techniques in the context of other parents who face similar challenges.”, feeling that there was a community to engage with.

Participants reported that the technology was helpful in several ways, allowing for both text and verbal communication options. Parents commented that “Communicating was easier than I thought it would be—especially with the texting option,” as well as being able to participate from different locations (including home, work, the car, or while traveling). Being able to access recordings of the mindfulness practices when a session was missed was also listed as an advantage of the technology: “The only challenge I encountered was with pre-existing commitments. I really appreciated having the recordings on Facebook to assist for those days.” However, there were some frustrations with the technology experienced by some participants, especially at the start. One parent described a “technology difficulty with my own equipment, my camera was broken, so I couldn’t be seen.” Another described that “I really disliked seeing my appearance on the screen during sessions.”

Several aspects of the intervention were described as particularly helpful including the learning of practical skills: “practical meaningful skills to apply for the rest of my life, that give me hope that I might be able to cope, and perhaps even cope well.” The unconditional accepting nature of group members and facilitators was also highlighted: “Moderators and other participants seemed to be very accepting. Although I often have trouble expressing myself, I didn’t have any fear in sharing with the group.”

Parents offered some helpful suggestions to improve the intervention, several of which leveraged technology. This included the suggestion of automatic reminders in their calendar for attendance and practice, the posting of recordings of sessions to review if they were missed, and more instruction and support to participate in an online forum for those less comfortable with using Facebook. During the session itself, one parent thought it would be helpful if the agenda could appear on the screen to guide the session.

As demonstrated in Table 3, parents reported reductions in stress and depression (DASS-14), as well as improvements in mindfulness (FFMQ), which were maintained at 3-month follow-up. They also reported improved scores in mindful parenting and self compassion and positive gain, and increased scores on the burden scale which suggests a reduction in overall burden between Time 1 and Time 2. Improvements were maintained between Time 2 and 3 for all measures except perceived burden.

Table 3 Parent outcome measures at baseline, post-intervention and 3 months follow-upTo assess whether changes reported between Times 1 and 2 in the virtual intervention differed from scores reported by parents who participated in the equivalent in-person mindfulness group intervention (Lunsky et al. 2017), an linear mixed-effects models were employed, with change between Time 1 and Time 2 scores as the dependent variable, type of intervention as the between-subject independent variable. The Time 1 ratings were added as a covariate in an adjusted model to account for baseline differences. Four cohorts of both the in person and virtual interventions were held and clustering by the cohort parents participated in was accounted for. Results suggest (see Table 4) that the two interventions did not differ in their outcomes at Time 2.

Table 4 Comparison of parent outcome measures at baseline and post-intervention between virtual and in-person groups

This study explored whether a 6-week mindfulness-based group intervention for parents of older autistic adolescents and adults held virtually was feasible, acceptable, and led to improved clinical outcomes. We were able to recruit enough people for the intervention, the technology was reliable and we were able to cover the same content as we addressed in a prior in person intervention. Overall satisfaction rates were high for those people who remained in the program, but there were some challenges with technology as well as barriers to participating for some caregivers because of competing responsibilities. Parents who completed the intervention reported improved mindfulness and reduced stress and depressed mood, and these reported changes were maintained at 3 month follow-up. The patterns observed in the current project were similar to parental reports in a prior in-person study.

This intervention was feasible in terms of recruitment and the technological aspects. Our recruitment strategy using social media and asking community autism agencies to circulate information led to sufficient numbers of people, but did not capture people equally across geographic regions. To best promote participation in a study like this, it would be important to allow for at least 2–3 months of time to engage with agencies and family groups so they could share information. It would be worthwhile to develop a research poster that adequately captures the details of the intervention, as well as the research component. About 40% of people who expressed an interest in the project either had younger children or could not attend on the day the intervention was being held. Although almost all of the parents who met criteria for the study and consented completed the baseline measures, the majority of non-completers opted not to complete post and follow-up study measures. It would be important in a larger trial to emphasize the importance of completing all measures regardless if they completed the intervention, and to provide incentives to parents who completed all of the measures, regardless of whether they opted to continue in the study or not.

With regard to adherence, just over half of the people who enrolled in the study and filled out baseline measures completed the intervention and one third attended 1–3 sessions. It would be important in future work to more closely examine why certain individuals do not stay in virtual groups and whether greater orientation to the purpose of the group prior, additional 1:1 technical coaching after the first session, or web-based resources would help with participation. Research on online treatments with other populations have reported that weekly reminders, individual coaching, and some in-person contact have all been helpful to improve participation. It would also be interesting to explore in further work whether parents who attend in-person intervention feel more committed to it, or have a greater sense of group cohesion than in a virtual setting (Gentry et al. 2019), making their continuation more likely. Although clinically we defined completion as attending 4 of the 6 sessions, future larger-scale research could also examine dosage effects and whether any benefits are apparent from engaging in fewer sessions.

In addition to being accessible to people who live remotely, certain aspects of online synchronous groups may be more appealing to family caregivers than in-person groups. These include the ability to mute oneself or take a small break to tend to a childcare issue, the time and cost saved not having to travel to a group or arrange childcare, and the ability to view recordings of the exercises that occurred online after session. Given the challenges parents experience and the shortage of time they have to tend to their own needs, the flexibility that comes with virtual-based groups can be important. As parents become more comfortable with technology, including older parents, the appeal of such modes of participating may become greater. Because of the COVID Pandemic, it is expected that many more families will be more accustomed to both virtual social connections and virtual health and social care.

Similar to in person caregiver mindfulness studies, reductions in distress were reported by parents in the current study. One intriguing finding was the reported shift in mindfulness scores, with parents reporting higher scores on three mindfulness measures, which were maintained at follow-up. Prior in-person mindfulness studies have been inconsistent in this regard. For example, while some in-person studies have reported improvements in mindfulness scores (Bazzano et al. 2015; Benn et al. 2012; Ferraioli and Harris 2013), Lunsky et al. 2015, 2017 did not find changes in mindfulness, following a similar 6-week intervention, even though distress scores decreased. It is possible that removing some of the in-person aspects of the intervention heightened the focus on mindfulness skills. Though not commented on by participants, the ability to practice mindfulness in the same setting where home practices take place may help with change and maintenance over time (Cooper et al. 2019). Alternatively, it is possible that parents already familiar with using online resources to participate in the group are more able to use online homework practices than parents who participate in person, or that the parents willing to participate in this type of intervention were more primed toward developing mindfulness skills. More research capturing the amount of practice and engagement with online materials would be important.

One important aspect of this study was the role of the parent advisor, which was not part of the earlier in-person study (Lunsky et al. 2017). Each of the three cohorts included two parents of autistic adults, who had participated in a prior mindfulness intervention. These parents, both of whom had prior experience supporting other parents, met with the clinicians leading the intervention each week, prior to and following the session, and also played a role in the sessions themselves, sometimes reflecting upon their own experiences, and closing each session with a relevant reading. In an era where patient-oriented research is increasingly recognized and valued (e.g., SPOR in Canada, PCORI in the US and INVOLVE in the UK) (Aubin et al. 2019), it is important that we further explore how parent advisors can help to improve delivery of services, and the impact of the parent role on therapists and group participants. Following delivery of these virtual groups, the parent advisors and lead clinicians have further adapted the parent workbook, as well as the session structure, in an effort to improve delivery, and are currently involved in the delivery and evaluation of this next iteration. To more fully study whether parents in an advisory role contribute to the gains reported here, similar groups without such advisors would need to be conducted as a comparison.

This study has several limitations which should be taken into account. Very little information was obtained from families who stopped attending sessions besides general reasons for dropping out. Although some changes were reported and the main mindfulness instructor was the same, the in-person group was not matched to the virtual group, individuals were not randomly assigned, and neither therapist nor participants could be blinded to their condition. A further controlled study with a larger sample is required. Greater emphasis on collecting trial data, regardless of adherence would be important and financial incentives would be helpful in this regard. These preliminary findings are based on a small group of keen parents eager to participate and may not generalize to other families, especially families less comfortable with technology or with limited means to access the required technology. It is worth noting that internet use across Canada is increasing with 91% of people older than 15 reporting using it, including 71% of seniors (Statistics Canada 2019). Few fathers participated in these groups, so it is difficult to comment on how effective it could be for them, or whether something tailored more specifically to men would be helpful. No information on treatment adherence was collected beyond attendance, no homework tracking, listening or viewing of mindfulness practices was completed, and no fidelity measures were used. Because each of the three cohorts had the same facilitators and parent advisors, using the same manual and parent workbook, we expect that sessions were delivered in a similar manner but it is possible that over time the team of two clinicians and two parents improved. Finally, it would be important to evaluate the role of parent advisor more formally.

Parent-focused interventions to promote their mental health are important when someone in the family is autistic. How to deliver such interventions should be informed by the families who would benefit from such efforts. Given the challenges with being able to make family-based interventions accessible to all families, further exploration of the practical, clinical and economic benefits of holding a synchronous group based mindfulness intervention virtually would be beneficial. Indeed, knowing whether there is any further benefit for parents to participate in mindfulness training virtually together as opposed to asynchronously alone is important to explore. Further evaluations could leverage technology to not only teach mindfulness skills but to evaluate which aspects of the intervention were most practiced and most helpful.

We wish to thank all of the parents who participated in our project and have helped us to further refine our virtual intervention for families.

This project was funded by the Autism Speaks Canada Family and Community Capacity Enhancement Grant.